On a cold November night fifty years ago, a massive freighter vanished beneath the waves of Lake Superior. Gordon Lightfoot’s haunting ballad captures the storm, the ship, and the 29 men lost on this day in 1975: an enduring story of courage, nature’s power, and memory that refuses to fade.

August of 1976

I was eleven years old when I first heard Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” The love of stories already had me firmly in its grip, and this was a story unlike any I’d heard before. Those eerie electric guitar lines, the mournful sway of the melody, and Lightfoot’s clipped, almost formal annunciation, all of it felt like wind in the wires and rain on steel. I could see the waves top the rail. I could feel the cold, merciless November wind.

Unbeknownst to me back then, Lightfoot’s song arrived only months after the tragedy itself. The freighter Edmund Fitzgerald had gone down on November 10, 1975, during one of the fiercest storms ever recorded on the Great Lakes. When Lightfoot released his single the following August, the wound was still fresh. There are two recordings of the song—Lightfoot re-recorded it in 2010 with slight lyrical changes—but for me, the 1976 original remains definitive. It has a rawness, a kind of reverent immediacy, that cannot be recaptured.

The Ship and the Storm

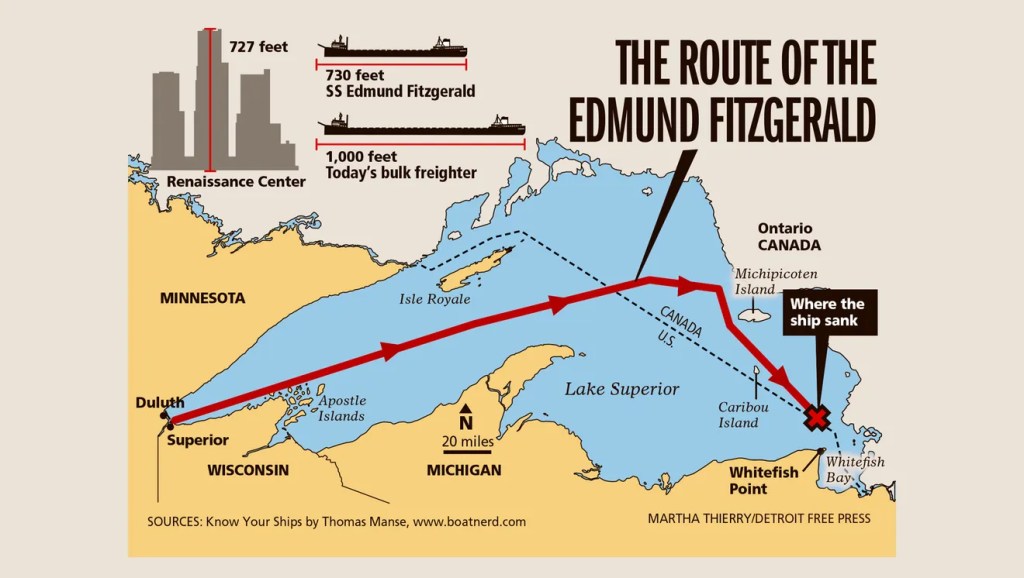

The Edmund Fitzgerald was no small craft. At 729 feet long and 75 feet wide, she was nearly as long as two football fields laid end to end, and as wide as a six-lane highway. From keel to deck, she stood about 39 feet above the waterline, roughly the height of a three-story building. When fully loaded with 26,000 tons of iron ore pellets bound for Cleveland, she rode heavy but proud, the largest ship on the Great Lakes at the time. Sailors and locals fondly called her “The Fitz.”

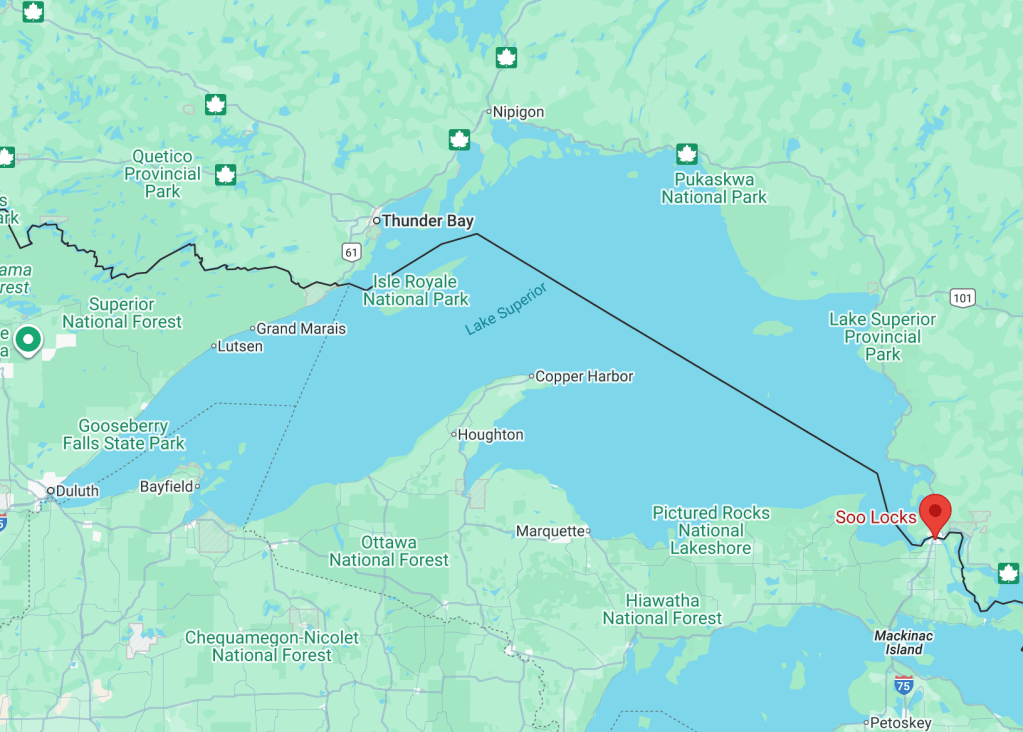

She was one of many freighters that plied those inland seas, carrying iron from Minnesota’s Mesabi Range down through the Soo Locks toward the industrial heart of the nation.

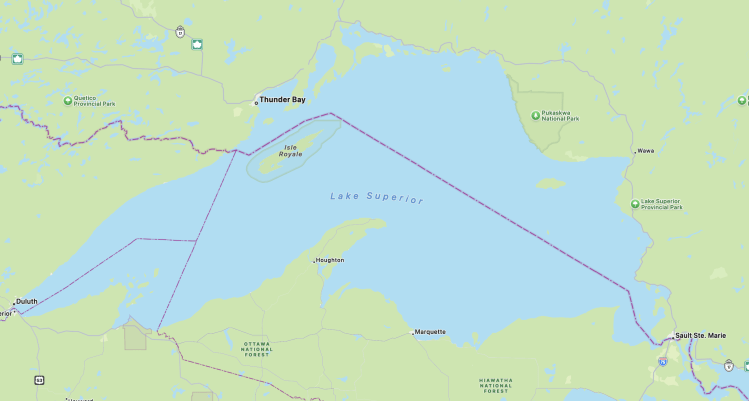

But Lake Superior is vast, 350 miles long, 160 miles wide, with depths reaching over 1,300 feet. To give perspective, Lake Superior covers more than 31,000 square miles, about the size of South Carolina.

By contrast, Louisiana’s Lake Pontchartrain spans only about 630 square miles. For readers outside the region, that means Superior is roughly fifty times larger. Standing on its shore, it feels less like a lake and more like a gray, inland ocean, cold and untamed.

When the storm struck on November 10, winds roared to nearly 60 knots (about 70 miles per hour), with waves cresting over 25 feet high, the height of a two-story house. That is the kind of water that can swallow a ship whole. Captain Ernest McSorley and his crew of 28 fought the storm for hours before vanishing from radar around 7:15 p.m. No distress signal was ever received.

Visualizing the Tragedy: What Really Sank the Edmund Fitzgerald

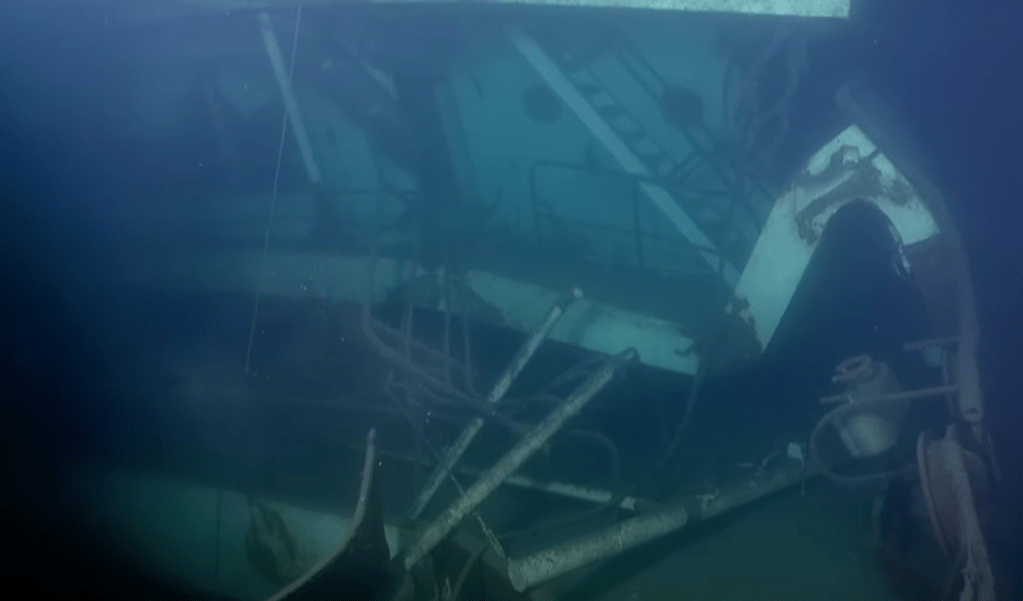

If you want to see what might have happened on that storm-lashed night, a compelling resource is this excellent 45-minute YouTube documentary “The Titanic of the Great Lakes: What Really Sank the SS Edmund Fitzgerald”. It walks through the ship’s final moments, examining missing sections of the hull, the impact trench beneath the bow, and how the massive freighter fought the waves before disappearing beneath Lake Superior.

Watching it, you get a tangible sense of the scale of the tragedy, the Fitzgerald, 729 feet long, caught in 25-foot waves, vanishing in over 500 feet of cold water. For anyone captivated by the song, the history, or the human story, this documentary is a chance to fall down the rabbit hole. You will see diagrams, dive footage, and analyses that bring the lake, the storm, and the ship to life in a way words alone cannot.

The Route and the Memory

This year, memorial events again honored that tragedy. At Split Rock Lighthouse, roughly 25 miles northeast of Duluth, Minnesota, a sold-out ceremony saw the beacon lit in memory of the crew. Across the lake, at Whitefish Point, Michigan, the southeastern tip of Lake Superior, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum hosted a public remembrance, with private family ceremonies following.

Standing on those shores, it is impossible not to feel the weight of distance. The Fitz was less than fifteen miles from safety when she went down, still fighting her way toward Whitefish Bay through the screaming dark.

And it is here that Lightfoot’s lyrics take over, where history meets elegy, and the story becomes something larger than the ship itself.

Lyric Breakdown: Verse by Verse

Lyrics ©1976 by Gordon Lightfoot, from GordonLightfoot.com

Verse 1

“The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

of the big lake they called ‘Gitche Gumee.’

The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead

when the skies of November turn gloomy.

With a load of iron ore twenty-six thousand tons more

than the Edmund Fitzgerald weighed empty,

that good ship and true was a bone to be chewed

when the ‘Gales of November’ came early.”

Lightfoot invokes local memory and folklore. Lake Superior, or “Gitche Gumee,” is more than water; it is a living presence that demands respect. He foreshadows tragedy and emphasizes the storm’s raw power.

Verse 2

“The ship was the pride of the American side

coming back from some mill in Wisconsin.

As the big freighters go, it was bigger than most

with a crew and good captain well seasoned,

concluding some terms with a couple of steel firms

when they left fully loaded for Cleveland.

And later that night when the ship’s bell rang,

could it be the north wind they’d been feelin’?”

The Fitz is introduced as a ship of pride and skill, manned by experienced sailors, all ordinary men soon to meet extraordinary danger.

Verse 3

“The wind in the wires made a tattle-tale sound

and a wave broke over the railing.

And ev’ry man knew, as the captain did too

’twas the witch of November come stealin’.

The dawn came late and the breakfast had to wait

when the Gales of November came slashin’.

When afternoon came it was freezin’ rain

in the face of a hurricane west wind.”

The storm comes alive. Wind through wires, waves over rails, and freezing rain make the peril immediate.

Verse 4

“When suppertime came the old cook came on deck

Sayin’ ‘Fellas, it’s too rough t’feed ya.’

At seven P.M. a main hatchway caved in; he said,

‘Fellas, it’s bin good t’know ya!’

The captain wired in he had water comin’ in

and the good ship and crew was in peril.

And later that night when his lights went outta sight

came the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.”

Human drama and loss are captured in the cook’s farewell, the captain’s warning, and the sinking itself.

Verse 5

“Does any one know where the love of God goes

when the waves turn the minutes to hours?

The searchers all say they’d have made Whitefish Bay

if they’d put fifteen more miles behind ‘er.

They might have split up or they might have capsized;

they may have broke deep and took water.

And all that remains is the faces and the names

of the wives and the sons and the daughters.”

Reflection on mortality, faith, and grief. Lightfoot honors those lost and those left behind with poetic and heartfelt words.

Verse 6

“Lake Huron rolls, Superior sings

in the rooms of her ice-water mansion.

Old Michigan steams like a young man’s dreams;

the islands and bays are for sportsmen.

And farther below Lake Ontario

takes in what Lake Erie can send her,

And the iron boats go as the mariners all know

with the Gales of November remembered.”

The scope widens to the entire Great Lakes. The lakes themselves are characters, alive and imposing, setting the stage for sailors’ struggles and memories.

Verse 7 – Part 1

“In a musty old hall in Detroit they prayed,

in the ‘Maritime Sailors’ Cathedral.’

The church bell chimed ’til it rang twenty-nine times

for each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald.”

Focus shifts to remembrance. Each bell toll honors a lost sailor, keeping memory alive.

Verse 7 – Part 2

“The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

of the big lake they call ‘Gitche Gumee.’

‘Superior,’ they said, ‘never gives up her dead

when the gales of November come early!'”

The song comes full circle, linking history, nature, and human storytelling. Lightfoot leaves us with reverence, reflection, and awe.

Remembering the Men and Their Story

Nearly fifty years later, The Fitz still refuses to fade from memory. Her bell tolls each November, both at Split Rock and at Whitefish Point, for the twenty-nine who never came home. And this year, a new work joins that legacy.

The Gales of November: The Untold Story of the Edmund Fitzgerald by journalist John U. Bacon (released October 7, 2025) gathers voices from families, friends, and shipmates to tell the story behind the song. It is being called the definitive account of the tragedy, part history, part tribute. Bacon explores how Great Lakes shipping fueled America’s economy, how the crew lived, and what may have truly happened that night on the water. The book is dedicated to the men and the families they left behind.

Closing Reflection

Stories like The Fitz are larger than any one song, book, or memorial. They live in the wind across the waves, in the lights of a lighthouse, and in the quiet toll of a ship’s bell. Lightfoot’s ballad, Bacon’s book, and the YouTube documentary each offer ways to remember, honoring the men and the families who loved them. Standing on the shore of Lake Superior, imagining a freighter the size of two football fields caught in 25-foot waves, it is easy to feel small, almost insignificant.

For me, The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald will always carry the sound of wind in the wires, the splash of waves over steel rails, and the names of twenty-nine men who never reached home.

That’s it for now. Thanks for showing up. It matters.

Until now I had no idea that ship was a modern one, just assumed it was a much older ship, perhaps from the last century. You don’t often hear of ships that size sinking these days, not like that. And yeah, it’s a beautiful haunting song…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad the article reached you. Thanks for stopping by.

LikeLike